EN PT/BR

Is a new economy possible? Perspectives from socio-technical networks

A first provocation

First, it is worth highlighting the relevance of the provocation made by Sabelo Mhlambi about the number of Black people present in this room. It is of utmost importance since the scope of the event is exactly to cause discomfort and questions, so I would like to make an initial contribution.

We must take advantage of this microphone and this space at the University of São Paulo, one of the main universities in the country, prominent in several ratings, including the rate of delay in the racial debate. It is immensely difficult to fully establish racial quotas here, and to think about the inclusion of Black, Indigenous, and marginalized people, which is a long-standing agenda and a struggle of student movements, especially the Black movement at this university.

We are in a country where 54% of the population is Black, a country built with Black blood and sweat, and possibly where your great-great-grandparents, non-Blacks, whipped my great-great-grandparents. Personally, I don’t want to discuss society, technology, and new paths through the white man’s lenses again. So I invite you to take a brief “neck test” around this room. Look around, look who is sitting behind you. And then I question: Where are the Black men and women in this debate to rethink society and technology?

The technologies from racial aspects

Having said that, I would like to talk a little about my research on social networks from the ethnic economy perspective. The theory of ethnic economy (Light, 2005, 2013; Gold, 1989) proposes to reflect the formation of ethnic groups that move together economically, in terms of employment, technical development support, and so on, always from those in their own ethnic group. Here in Brazil, for example, there are Korean, Japanese, Italian, and Armenian communities, among others, that operate within this logic. So, I started to observe that the movement of Afro-entrepreneurs was a phenomenon very similar to this line of thinking.

But before I share some of the research findings, I present a parallel with the younger generation of Afro-entrepreneurs and the story of my mother, who is also the inspiration for this work. My mother, as well as many Black mothers, is from Bahia, with little schooling, and who came to São Paulo between the 1970s and 1980s to try to “make a living.” In the capital of São Paulo, she started working as a housekeeper, but she also carried out other activities for complementary income. At that time there was possibly no discussion about entrepreneurship, nor was there any discussion about Afro-entrepreneurship. Then, more recently, around the beginning of the 2000s, several movements and groups of Afro-entrepreneurship flourished, such as the Feira Cultural Preta [Black Cultural Fair], the AfroBusiness, the Black Rocks Startup, and the Brasil Afroempreendedor [Afro-entrepreneur Brazil], among others, that collectively intend to discuss and establish connections and solutions for Afro-entrepreneurs.

It is, therefore, possible to make some connections with my mother’s story, but with a generational divergence. These young Afro-entrepreneurs are mostly the first of their families to enter university and they choose entrepreneurship based on their technical backgrounds as accountants, lawyers, administrators, and other various professions.

Thus, the first observation in my research is precisely the generational question: Who is an entrepreneur by necessity, which is the case of my mother, who needed extra money; and by opportunity, which is the case of these people who are now trained and have the opportunity to choose which career to pursue? However, it is important to point out that many of the choices made by the current generation also come as a result of a labor system that is still racist and exclusionary. Therefore, if the individual does not get an opportunity in the so-called formal labor market, then the individual creates their own opportunities.

Besides the generational difference, we also observe the relationship between the use of analog and technological media for communication and information. The development and use of technology is not new to Black people, as Brazil’s economy was built from the beginning on the work of this population that brought from Africa a very well-developed technical knowledge (Cunha Jr., 2010). Black technologies are responsible for optimizing services from tooling, clothing, accessories, agricultural technologies, pharmacology, textiles, construction, use of soap, wood—everything that was brought from the African continent and used in the construction of the country.

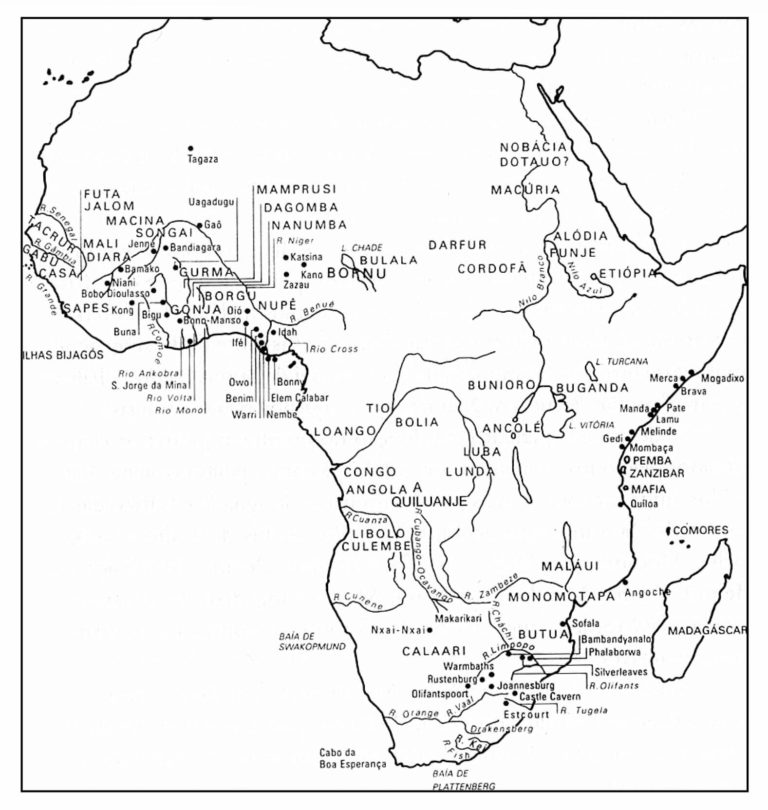

Africa in 1500.

Leather sandal and bag produced in Africa.

Warriors of Waaloo (Cunha Jr., 2010).

Thus, to exercise a contemporary reflection on Afro-entrepreneurship as an ethnic group that organizes itself to develop creative solutions on the economy, it is of utmost importance to speak of racism as a structural and structuring mechanism of society. As professor Silvio de Almeida states:

The search for a new economy and alternative forms of organization is an impossible task without racism and other forms of discrimination being understood as an essential part of the processes of exploitation and oppression of a society that intends to be formed. (2017, p. 198)

From the Internet and technology, these Afro-entrepreneurs form new communities, provide technical training, experiences, and occupy important spaces to discuss issues that permeate racism. As Munanga (1999) explains, the various contemporary Black movements, and this includes the movement around Afro-entrepreneurship, are constantly rescuing their cultures, their respect and values of their participation in building society and strengthening their identity. This is one of the aspects of the ethnic economy in all ethnic groups, as we see in branches such as cuisine and its various restaurants with typical dishes, clothing, aesthetics and beauty, and symbols, among others.

Building networks and communities from the appropriation of the Internet and technology is also a way of surviving from an economic point of view. But it is worth emphasizing that studying Blackness and technology presupposes an overlapping of themes, among which the political and social aspects are inseparable from any debate that one may aim to look at.

To name some examples, let us remember Rafael Braga’s case. The only one arrested in the 2013 protests in Rio de Janeiro for carrying a bottle of cleaning product, he was not even taking part in the protests. Still, on another occasion, policemen alleged wrongly that Braga was in possession of drugs in a police raid. The case generated a great commotion in the Black community and its sympathizers, from social networks and the Internet, which gave rise to the Facebook page called “30 dias por Rafael Braga” [30 Days for Rafael Braga], in which several professionals, students, and other engaged people gathered to give visibility to the case (Oliveira et al., 2017).

Solidarity and indignation network in the Internet: the case of “Freedom for Rafael Braga” (Oliveira et al., 2017).

Another example covers the one-year analysis of the murder of councilwoman Marielle Franco from conversations generated on Twitter. We observe a network composed not only by the Black community but also by the feminist movement, politicians and personalities from other countries who have established conversations, especially as it relates to the racial issue, one of Marielle’s main guidelines as an activist and politician (Lima & Oliveira, 2019).

Marielle Present: the social networks one year after the murder of the Rio councilwoman (Lima & Oliveira, 2019).

In an example about Afro-entrepreneurship, we have an analysis of the fifteen years of Feira Preta [Black Fair], one of the oldest events about the subject in Brazil. Among the facts observed, we see that Feira Preta not only talks about selling and buying products, or technical aspects about commercial exchanges, but some elements reinforce Black identity, as pointed out above, such as music, aesthetics, political and social discussions, and, especially, more specific issues of Black women (Oliveira, 2018).

Afro-entrepreneurship from social networks

In the survey “Redes sociais na Internet e a economia étnica: Um estudo sobre o afroempreendedorismo no Brasil” [Social networks on the Internet and the ethnic economy: A study on Afro-entrepreneurship in Brazil] (Oliveira, 2019), in which, among other methodologies, an online survey was conducted to understand the profile of Afro-entrepreneurs, 69.5% of the interviewed were Black women. From this data we can elaborate on some questions: Are these women Afro-entrepreneurs because they have chosen to be, or are they still the primary source of financial support for their families? Is it a manifestation of the return to matriarchy or the portrait of an unequal labor market in terms of gender and race?

Other data reveals that interviewees are young people between 26 and 41 years of age (58.6%) and are registered as self-employed. Regarding income, most of these people earn up to R$5,000.00 and are formally registered as Individual Microentrepreneurs. From this perspective, questions about job insecurity, the dismantling of labor rights, and the income difference between Black people and non-Black people arise as a warning.

Another very interesting fact is that 92.2% of the respondents take part in or are interested in social movements, especially Black rights movements. Here again, we see that this is not only about commercial exchanges, but there is the addition of participating and debating the political and social context in which Black people are inserted and making this movement not only a way to survive in a capitalist system, but also a way to highlight these problems.

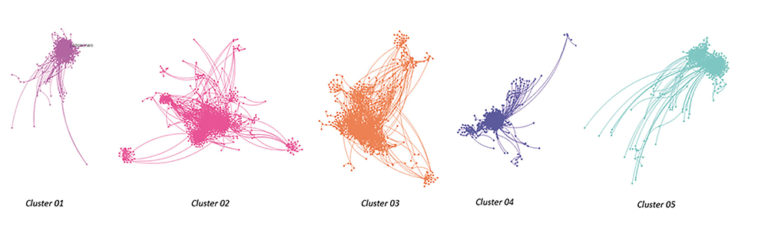

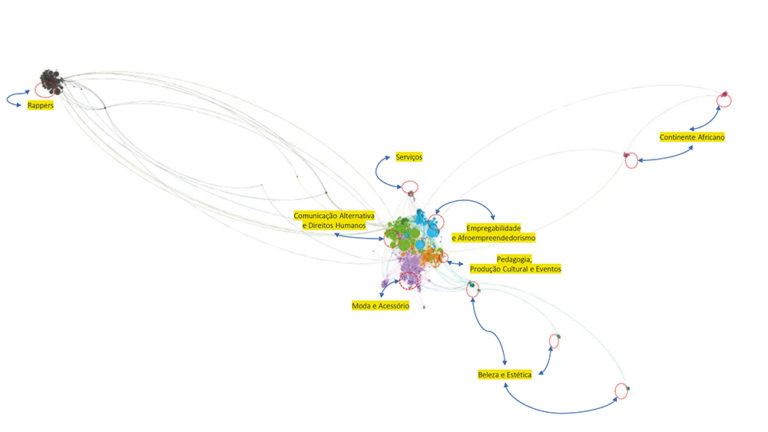

When we look at the network formed from Afro-entrepreneurship on Facebook pages, as shown in Figure 8, we can see the structures and relationships in the digital context, and then we can answer questions such as: Which pages, projects, and associations connect most and talk most to each other? What are the themes that are not necessarily related to these exchanges, but that symbolize a whole in the construction of Black peoples’ identity?

Structure and relations of Afro-entrepreneurship based on the analysis of social networks in the Internet (Oliveira, 2019).

We have then a rappers’ community, and their own communication with racial demarcation, fashion, accessories, and services, a specific community on employability, others on beauty and aesthetics, and relations with the African continent through the Chambers of Commerce.

Therefore, the primary function of Afro-entrepreneurship, which is focused on uniting commercial exchange to the construction of one’s identity, is what the dialogue between the Brazilian rapper Mano Brown and his mother illustrates, in a song by Racionais MC’s: “From an early age our mother says: ‘Son, because you are Black, you have to be twice as good.’ ‘How are we going to be twice as good if we are 300 years behind?’”

The main characteristics of Afro-entrepreneurship go beyond technical aspects but are also dedicated to overcoming demands occasionally developed by social, political, and structural problems. Afro-entrepreneurs use emotions that demarcate their ethnicity in their business: they are outraged and believe in the ability of their Afro-entrepreneur networks to change scenarios. For Afro-entrepreneurs, to undertake is to build their histories’ past and present, given their living conditions. The practice of Afro-entrepreneurship also demarcates disparities in the act of entrepreneurship between Black and non-Black people, especially in what refers to the social, economic, and political capital of these groups.

Thus, we conclude that to think of a new possible economy taking into account the technological context, it is of utmost importance to listen and to respect those who resist and innovate since the first slave ship arrived in this land.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Silvio L. de. Capitalismo e crise: o que o racismo tem a ver com isso?. In: OLIVEIRA, Dennis (org.). A luta contra o racismo no Brasil. São Paulo: Fórum, 2017.

ALMEIDA, Silvio L. de. O que é racismo estrutural?. São Paulo: Letramento Editora e Livraria, 2018.

BOYD, Robert L. The organization of an ethnic economy: Urban Black communities in the early twentieth century. The Journal of Socio-Economics, v. 41, n. 5, pp. 633-641, 2012.

BOYD, Robert L. Urban locations and Black metropolis resilience in the Great Depression. Geoforum, v. 84, pp. 1-10, 2017.

BURDICK, Anne et al. Digital Humanities. Mit Press, 2012.

CUNHA Jr., Henrique. Tecnologias africanas. Rio de Janeiro: CEAP, 2010.

DANIELS, Jessie. Race and racism in Internet studies: A review and critique. New Media & Society, v. 15, n. 5, pp. 695-719, 2013.

GOLD, S. J. Chinese-Vietnamese entrepreneurs in Southern California: An enclave with co-ethnic customers? In: Proceedings of the American Sociological Association, Anais. San Francisco, 1989.

LIGHT, Ivan. Global entrepreneurship and transnationalism. In D. Leo-Paul (org.). The Handbook of Research on Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship: A co-evolutionary view on resource. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2007.

______. The ethnic economy. In N. Smelser e R. Swedberg (org.). The Handbook of Economic Sociology. Princeton EP & Russel Sage, 2005.

LIMA, Dulcilei da Conceição; OLIVEIRA, Taís Silva. Marielle Presente!: As redes sociais no marco de um ano da morte da vereadora carioca. Anais do 8º Congresso Compolítica. Brasília, 2019.

MUNANGA, Kabengele. Negritude – Usos e sentidos. 3ª ed. 1ª reimp. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2012.

OLIVEIRA, Taís. Redes sociais na Internet e a economia étnica: Um estudo sobre o afroempreendedorismo no Brasil. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências Humanas e Sociais) – Programa de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade Federal do ABC, 2019.

OLIVEIRA, Taís. Redes sociais na Internet, narrativas e a economia étnica: Breve estudo sobre a Feira Cultural Preta. In: SILVA, Tarcízio; BUCKSTEGGE, Jaqueline; ROGEDO, Pedro (orgs.). Estudando Cultura e Comunicação com Mídias Sociais. Brasília: Editora IBPAD, 2018.

OLIVEIRA, Taís; DOTTA, Silvia; JACINO, Ramatis. Redes de solidariedade e indignação na Internet: O caso “Liberdade para Rafael Braga”. Anais do 40º Encontro do Intercom. Curitiba, 2017