EN PT/BR

INTRODUCTION

I, the [hu]man of color, want only this:

That the tool never possess the [hu]man.

—Frantz Fanon, “Black Skin, White Masks” (1952)

Fanon made this plea just as the first digital computers were being built in the United States of America. Almost seventy years later, information technologies built on artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are being woven tighter into social and civic fabrics worldwide, encoding colonial injustices into global information infrastructures. The software tool has come to possess the human of color.

Who builds these tools? Much new work in AI and ML is informed by an understanding that is rooted in the cultural and legal values of the Global North. But the uses of AI and ML are situated in different cultural, political, and geographical localities, where there are also differences of power and agency among the people who are interacting with such technologies. Too often technological futures are being determined solely by those with advanced training in technological systems and with a flattened sense of the social landscape.

As Audre Lorde said in 1979, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Thus our work, as critical researchers, artists, and activists, must start by dismantling these tropes to build a collective understanding of these tools together. This publication is a collective response to these and many other questions, in order to propose an affective reframing of the possibilities of machining intelligences.

The origin of this publication:

The Affecting Technologies, Machining Intelligences event

This publication serves as the careful record of just three days—a time when an unusual set of people was in the same room and started a conversation together so rich and urgent that we, as organizers, thought it deserved to be brought to a wider audience. Hence this book.

In these pages we collect the presentations and projects first presented at the Affecting Technologies, Machining Intelligences (AT/ MI) event, held from February 5-7, 2020 in São Paulo. This event brought together a diverse coalition of people whose work bridges technology, computing, art, and humanities/social research. Most of the invited guests were connected to the Global South, and/or decolonial, feminist, and Indigenous ways of thinking. They shared an activist and collaborative disposition, especially through participatory and performative ways of constructing knowledge, research, and artistic practice. Our event showcased their work with invited talks and provided time for collaboration via Q&A, discussion, and workshops.

The event organizers (Dalida María Benfield, Bruno Moreschi, Gabriel Pereira, and Katherine Ye) are members of the Affecting Technologies working group, which met under the umbrella of the Center for Arts, Design, and Social Research (CAD+SR). We had organized our first gathering at Aalto University (in Helsinki) called Archipelagos: Maps of the Moving World, which also convened researchers, activists, and artists. This gathering served to test-run some of the structures of collaborative making that we would put into place at this São Paulo convening.

The event in Brazil unfolded in spaces provided by our local partners at the University of São Paulo, the Institute of Advanced Studies (IEA-USP) and the Innovation Center (Inova-USP). The IEA-USP, which served as the place for our morning presentations, is an interdisciplinary institute that brings researchers from the university and other institutions for discussing urgent questions for science, culture, and society. Inova-USP, where one of the organizing members (Bruno Moreschi) is based, served as the space for our afternoon discussions, workshops, and exchanges. We held workshops in the room of the recently created GAIA (Group on Art and AI) / C4AI.

At the Institute of Advanced Studies of the University of São Paulo (IEA-USP), during the mornings of the three days of the event, the formal presentations by the invited researchers took place.

Source: Leonor Calasans/IEA-USP

This publication and Its moving parts

First, this publication includes a summary of the collaborative event and the pedagogies it involved, including the group work we constructed together in sessions, workshops, and performances. It is also important to point out that this current description was written by many hands, including the participants themselves. Following the introduction are texts by each of the presenting participants. These texts were written especially for this publication, and most are expansions of their talk given at the event. The content is organized into four sections, each representing one way of reimagining our relationships with computing.

The first section, Imaginaries and Countercurrents, is concerned with picking out the tropes behind contemporary computational systems to consider other ways of thinking about them. This section begins with Katherine Ye’s piece “Silicon Valley and the English Language,” which deconstructs the simple phrase “We build human-centered tools that scale” to shed light on the Silicon Valley culture it arises from and to propose ways to create new computing countercultures. The following chapter, “Overcoming the limits of rationality in humans and in rational machines through ubuntu’s relational personhood,” by Sabelo Mhlambi, rethinks rationality by incorporating Sub-Saharan African epistemologies and ontologies. To Mhlambi, rethinking technology means decolonizing it by considering, for example, alternative perspectives that focus on personhood, which he draws from Ubuntu. Next, in “Teaching Technics: Three (Re)Arrangements and Relanguagings,” Dalida María Benfield proposes ideas for thinking critically about the potential of pedagogies and technics in times when both education and technology are being “positioned as levers for modernization and development.” Finally, in “A Preview of Divergent Search,” Rodrigo Ochigame showcases some experiments with designing alternative algorithms for search by centering divergent perspectives, rather than maximizing a typical notion of utility (e.g. finding what is popular or trending).

The second section, Algorithms at Work, considers the relationships between mechanical automation and human labor. The text “What Is being said about digital work, AI, and the future of work,” by Rafael Grohmann, discusses the contradictions of work in the digital time, while also hinting at the possibilities of new, fairer ways of working together. Following that, GAIA (represented by Bruno Moreschi, Guilherme Falcão, and Bernardo Fontes) showcases their project Exch w/ Turkers, which aims to highlight the human layers of AI-flavored gig work. Finally, Amanda Chevtchouk Jurno discusses in her text “Journalistic Mediation × Algorithmic Mediation” the platformization of journalism, and how this process has led to the transformation of news mediation into an algorithmic process of filtering and selecting.

The third section, Image and Intelligences, explores the ways machines see the world and how we can critique or reimagine them. The first text, “The Truths of Deepfakes,” by Giselle Beiguelman, addresses the construction of deepfakes: how they represent and question our new visual cultures. Next, Gabriel Pereira presents “Alternative Ways of Algorithmic Seeing-Understanding,” in which he discusses the role of computer vision in the world as a form of seeing-understanding, while also thinking about what these machine visions could be if they were otherwise. Finally, Didiana Prata closes this section by discussing “Calendar of Dissenting Images: A Graphic Memory of Brazilian Politics on Instagram,” presenting her artistic project that creates novel ways of visualizing the politics in Brazil based on social media data.

The fourth section, Community and Solidarity, brings together ideas for rethinking our relation with technology based on feminist and decolonial perspectives on community, solidarity, and pedagogy. Jennifer Lee’s piece “Creating Community-Centered Tech Policy” presents a history of technology and power in the U.S., then discusses some projects led by the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington (ACLU-WA) that center communities in regulating technologies. Next, Taís Oliveira presents her study “Is a New Economy Possible? Perspectives from Socio-Technical Networks,” which focuses on Afro-entrepreneurship in Brazil, proposing possibilities of creating new economies based on solidarity and identity. Finally, Silvana Bahia showcases her work with the Olabi makerspace and the many projects this organization has supported in “For More Diversity in Technology.”

Source: Workshop participants

The publication concludes with a textual experiment by Sylvain Souklaye that makes visible the invisible work of production and facilitation for the event and this publication (more details on the front endpaper on page 26). In a single text, Souklaye combines many emails (those exchanged by the organizers in the four months leading up to the event) into a composite voice that speaks of the labor of organizing.

Collaborative making sessions

We started in the IEA-USP center, using the Alfredo Bosi room. During all three mornings of the event, we would meet in this place for the talks, which were followed by Q&As. These presentations were all recorded and attended by the public. During the afternoons, we met at the lovely GAIA space at C4AI / Inova-USP, where we held the collaborative making sessions and workshops. This space, due to its size and openness, was particularly useful for us, as it allowed people to move in and out, but also for different groups to form without running out of room. The collaborative making sessions were facilitated by Dalida María Benfield (DMB), Bruno Moreschi (BM), Gabriel Pereira (GP), and Katherine Ye (KYE). We have different levels of expertise in facilitation—some of us have more experience in facilitating public education, while others have worked more closely with community organizing or artistic practice.

Day one

During the first collaborative making session, we wanted the public to get to know each other, so we started with two exercises meant to introduce people to one another.

The first exercise was called “Introduce your partner.” We split into pairs and asked each person to briefly interview the other, before introducing their partner to the big group. We asked them to write, during the interviews, a few keywords about their partner’s work on separate post-its, which they were going to use in the next step.

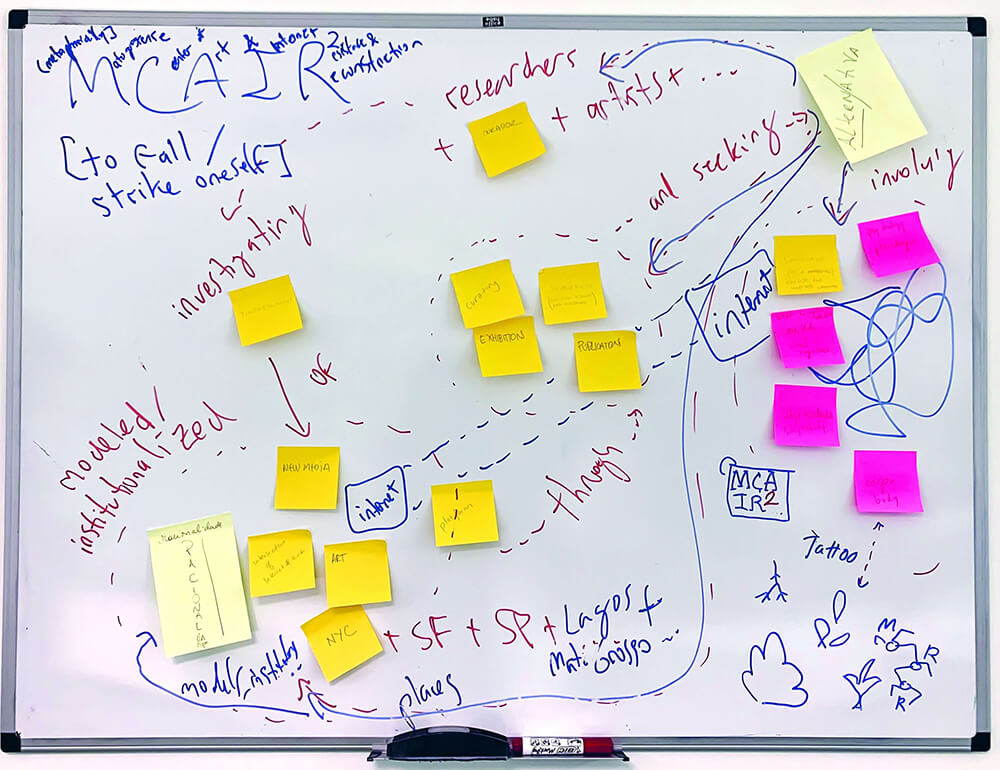

The upcoming exercise was one called “Mapping a constellation of our work,” in which we split everyone into small groups of around five people, then we asked each group to arrange their post-its in space and draw the ways that the keywords relating all of their work related to each other. Finally, we asked each group to present their map to the big group, and then we discussed each map. These conversations became very captivating, which was a great sign that people were engaging with each others’ work. Moreover, all of the mapping constellations were very unique: while some needed the whiteboard and arrows, others used the floor and proximity.

As facilitators for this session (KYE + GP), we took notes on the subjects that emerged from the discussions and arrived at six main themes:

1. Evading institutional capture (of diversity)

2. How does the subjective clash with the algorithmic?

3. Different modes of alternatives

4. How is art a technology?

5. Too fast for language

6. How can you hack it if you can’t signify it?

We challenged participants to pick one of these provocatively-phrased themes and make something quickly in the intervening half hour. The idea was to serve as a warm-up for the collaborative making sessions to come. The groups produced an intriguing collection of prototypes.

For “How does the subjective clash with the algorithmic?”, one group proposed a startup that would “burst your filter bubble” by invading your apps to suggest things that you wouldn’t have usually picked. For example, “If you would normally swipe left, it would swipe right for you.”

For “Too fast for language,” one group proposed a startup called “Otherment” that would name feelings and situations that new technology created and language had not yet caught up to. For example: A font made of someone’s handwriting would be called “Handtypus.” A computer-generated face that you think is real, but does not exist, would be named a “Trojan face.”

For “Evading institutional capture,” one group proposed a boxlike mechanism that could capture smiles from the real-life, turning them into more-than-real representations.

For “Different modes of alternatives,” one group discussed the concept of “Sankofa,” symbolized by the African icon of the goose who looks backwards as its body moves forward, and proposed that new technology be developed via a return to ancestral roots.

For “How is art a technology?,” one group moved outside and conducted a participatory performance centered on a found object of a log located at the University of São Paulo campus. During the performance, the group asked people to say words to describe the log, joining into a chorus, and questioned the relations between materiality, technology, and performance practice. The log, which came from a lightning strike on a nearby tree, was moved to the GAIA room, and accompanied us for the rest of the event.

Day two

On the second day, we wanted to help people find partners to collaborate with, so we started introductions with the following prompt by going around the big group: “Tell us about where you’re trying to go, what/who you need to get there, and what you might be able to offer.” We suggested that people take note of the ones they might want to collaborate with or contribute resources to.

Then we opened up into a few hours of unstructured time where participants could do whatever they wanted. We suggested only that people try and talk to different participants, rather than working with the first groups that happened to form (e.g. if people were sitting close to each other). We, the facilitators (GP + KYE), asked people to move around once we noticed they stayed in the same group for too long, in order to create more movement and exchanges in the space. By the end of the assigned time we saw several groups coalesce. These groups started working together, also thinking about the potential of presenting whatever they built/constructed/discussed by the end of the next day, when we would have performances and presentations.

During the evening, we had two workshops. The first one, run by Lucas Nunes and Rafael Tsuha, was entitled “A Crack Inside the Museum—Problematizing the Computer Vision of Commercial AIs.” They asked participants to use the Recoding Art platform as a way to find “unexpected results” in a museum collection, which would then be used to create a zine showing these multiple ways of looking at art. The workshop and its discussion aimed to demonstrate the use and misuse of AI in a visual arts context, and potential alternative ways of employing it, which provocatively considered the poetic and comedic “mistakes” that AIs make.

The second workshop, run by Bernardo Fontes and Bruno Moreschi, asked participants to roleplay Amazon Mechanical Turk workers to embody invisible labor. Participants came to a table full of microtasks, such as “Take a photo of yourself and submit the results,” for which they received imaginary money on the order of cents, and were alternately berated and praised by the facilitators, who took on the role of Amazon. At the end, participants compared who had made the most money and discussed the particular problems of doing “clickwork” online. There was, for example, a lot of discussion on the potential for requesters to reject tasks, the possibility for workers to support each other, and the difficulty to understand what tasks were for. The main contribution of this discussion was to think about how this virtual labor is actually real and operates in a physicality that cannot be ignored.

Day three

On the last day, participants engaged in one final collaborative making session. The room was filled with the frantic energy of construction as people compiled work into zines, rehearsed performances, and wrote code. Then we segued into performances and presentations by the five groups.

In the afternoons and evenings, the group worked collectively in the room of the Group on Artificial Intelligence and Art (GAIA), part of C4AI, Inova-USP. At this place, the network of researchers not only programmed and performed digital actions, but also created physical interventions in the physical space of GAIA.

Source: Workshop participants

First, Gabriel Lemos and André Damião performed a sonic piece called Guerra não linear [Nonlinear Warfare], based on the Russian strategy of hybrid warfare that employs disinformation and cultural subversion to disorient military and civilian targets. Originally composed for the 9th edition of the Festival Novas Frequências, which took place in Rio de Janeiro (December 2019), the composition Guerra não linear explores the different relations between noise, (counter)information, acoustic space, and architecture. Through loudspeakers and portable sound devices, musicians and the public led a procession guided by verbal scores and urban paths. For our event, the duo adapted the mobile format into a reduced presentation, making use of electronic devices and percussion to occupy the acoustic space of GAIA.1

Next, Sabelo Mhlambi presented a work in progress on his platform, CitePOC, for encouraging citations of work by Black scholars. CitePOC enables users to create and find references to academic work by scholars of color. The platform currently focuses broadly on ethics, technology, and policy.

Next, a group composed of Luciana Santos Barbosa, Amanda Chevtchouk Jurno, Rafael Tsuha, and Katherine Ye presented a performance based on the themes of orality, literacy, and subjectivity. The question was: How can a transcript notate the different subjectivities of each person speaking, rather than flattening words into affectless writing? Three members of the group performed readings of different texts. With each reading, the text of the reading was transcribed and projected according to heuristics for the affect of the person: the tilt of the word according to the tilt of the person’s head as they said it, and the size of the word according to the volume. (The group wrote custom software in the browser using deep learning for transcription and computer vision.) Finally, the group invited audience members to come up and perform into the interface. One person came up and sang in Spanish; another one came and spoke in Zulu.

Next, a group composed of Bruno Moreschi, Rodrigo Ochigame, and Bernardo Fontes presented an initial prototype version of a map system called DesRota that, rather than finding the shortest path between points, found paths that tried to maximize serendipity, to show the user a new way to live life. The idea was that if the software thought you were likely to (say) visit a Buddhist temple in New York, it might take you to visit several sites of other religions on the way. In other words, the system aimed to create paths that maximized divergence rather than efficiency.

Finally, a group composed of Dalida María Benfield, Jennifer Lee, Gabriel Pereira, and Carol Berger presented four pieces examining the theme of how activists could intervene in unjust Big Tech practices by wielding their own power. The first piece was a zine examining the theme of refusal, in which participants were asked to freely contribute their thoughts on refusal and resistance to technologies, and respond to others’ ideas.

The second piece was a participatory installation where people could write what they were for and against. By marking their views on what technology should or shouldn’t become, participants discussed how we can better shape our technological futures.

The group also presented a participatory performance, in which people used their bodies to playfully consider how technologies shaped their relation with the world, and how they can reframe their responses to it. The questions and answers written in the installation became material for the performance: agreements and disagreements moved the bodies of the participants who were lined up in the same area of the room.

The last piece was a participatory performance that asked people to sit at a negotiating table as either a member of a marginalized group or a member of a Big Tech coalition. The design of this work was inspired by Augusto Boal’s work Theatre of the Oppressed. The group members facilitated several scenes from their own experiences advocating for marginalized communities, such as encouraging community members to pressure companies with boycotts, and showing how a representative of a large tech company might make a promise and then renege on it. As participants took turns speaking and listening, they experienced how it felt to be on both sides of the table, and imagined together what kinds of modes of collaboration and opposition could generate better ways for dialoguing.

At the end, Jennifer Lee and Katherine Ye led us in a collaborative “rainmaking” session. By making a crescendo and diminuendo of sound together with our bodies (by rubbing palms, snapping fingers, drumming thighs, pounding feet, and back around), the exercise gave us an embodied sense of our ability to work together to create collective power.

We ended with a late night with drinks together in a typical “boteco” (a traditional type of bar in Brazil), in the center of São Paulo. This was not the end, but a beginning!

Source: Workshop participants

Toward a counterculture

We hope you feel a life in these pages, a life that cannot be captured in print. That energy vibrating between the lines comes from those conversations that started back in São Paulo in February 2020, where we began talking together during lunches, dinners, breaks, in the subway, in our shared rooms, and over email, challenging and deepening our ways of thought together. As organizers, we prize these exchanges as productive collisions, as the signs of life of a new counterculture of computing that we hope to nourish. It’s a little world, and we hope just one of many. As the Zapatistas say, “The world we want is one where many worlds fit.” We invite you, the reader, to consider how our world fits with yours.

On the closing night of the event, artists Gabriel Lemos and André Damião performed the Guerra não linear [Nonlinear Warfare] performance

Source: Workshop participants

1 A video of the performance is available here: