EN PT/BR

Creating Community-Centered Tech Policy

I work in the U.S. on building community-centric technology policy at the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington (ACLU-WA). I’m here to share my experiences working on policymaking in the U.S., and also to learn about policymaking that is more expansive than the voices in the Global North.

First, I’ll provide some background on what the ACLU does and what we do in our technology and liberty work. The ACLU is a nonprofit organization and the biggest public interest law firm in the U.S. We work in the courts, in legislatures, and in communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to everyone in the U.S. by our constitution and our laws. We work on many different intersecting issue areas spanning healthcare, immigration, technology, gender justice, and reproductive care. Our overall objective in doing our technology and liberty work is to protect and advance people’s civil liberties and people’s constitutionally protected rights in the face of truly game-changing technology. We focus on prioritizing the voices of historically impacted communities and pushing for these communities to have real decision-making power, to choose if and how technologies are used. We do this work in four key ways:

– Pushing for new policies and laws to create safeguards around technologies, or to stop the use of them altogether;

– Pursuing litigation where existing laws are unjust and work with our legal team to remedy harms;

– Organizing with communities and those historically impacted by technologies to center impacted voices in pushing for change; and

– Engaging in corporate advocacy, where we support the work of technology activists within companies and outside of them.

I’ll be centering today’s discussion on building community–centric technology policy and start by first providing a little bit of context about technology, values, and power. Then I’ll be presenting three case studies: the Tech Equity Coalition, the Seattle Surveillance Ordinance, and community capacity-building projects.

Technology, values, & power

Technology is often presented as the panacea to many of our world’s problems, with the assumption that more technology will make everyone’s lives better, not worse. And technology does seem beneficial in a lot of way—it makes things faster, cheaper, and more interconnected. But the key question that we need to ask is: Does making things faster, cheaper, and more interconnected make things “better”? And, if the answer is yes, for whom does it make things better?

Cartoon by P.S. Mueller.

Source: P.S. Mueller

This is an important question to think about because, much like anything else designed by humans, technology isn’t “neutral.” Every technology reflects a set of value choices made by people, and often people in positions of privilege and power. You can see this not only in the way that we design technology, but also in the way we design everything else around us. Examples of hostile architecture are displayed in Figure 2 where you see bolts installed on steps in France, as well as a rainbow bench with rails in Canada. The design of these objects deters unhoused people from being in public. There is a motivation in the way these tools were built and, similarly, there is a motivation in the way technology has been built because humans who hold different values, biases, and incentives build these technologies.

Hostile architecture: bolts installed on steps in France and a rainbow bench with rails in Canada.

Source: Wikipedia, DocteurCosmos / CC BY-SA 3.0, Twitter @isaacazuelos

We need to understand that every technology is released into a context of structural inequity. Here are two definitions of structural inequity, which describes the system of privilege created by institutions that disadvantage some people over others:

Structural inequity: personal, interpersonal, institutional, and systemic drivers that create systematic differences in the opportunities groups have, leading to unfair and avoidable differences in outcomes.

Another definition: “Structural inequality is a system of privilege created by institutions within an economy. These institutions include the law, business practices, and government policies. They also include education, health care, and the media.” (Kimberly Amadeo)

There is a long history of technology impacting different people differently. What we’ve learned throughout history is that every time a new technology has been built, it has had disproportionate impacts on the most marginalized in society, whether or not the technology was intended to do so.

In 1713, New York City passed a Lantern Law requiring Black and Indigenous people to illuminate their faces at night, which encouraged white citizens to enforce systems of slavery and incarceration, and candles were the technology of the time.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the U.S. government subcontracted with IBM, which provided its Hollerith punch card machines to surveil and target Japanese Americans via census data. Japanese Americans were surveilled and put on custodial detention lists for nearly a decade prior to being unconstitutionally incarcerated during World War II. Further, these are the same IBM Hollerith punch card machines that were used around the same time by Nazi Germany to identify Jews, as well as other ethnic, religious, political, and sexual minorities.

Members of the Mochida family awaiting evacuation bus. Identification tags are used to aid in keeping the family unit intact during the evacuation.

Source: Dorothea Lange / U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

In the 1950s and 1960s, the FBI surveilled Black civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., via wire-tapping machines and photos taken by informants. The FBI’s COINTELPRO (short for Counterintelligence Program) targeted civil rights leaders and Black Panther Party leaders and attempted to “neutralize” them via assassination, imprisonment, public humiliation, and false crime charges.

The “suicide letter” that the FBI mailed anonymously to Martin Luther King Jr. in an attempt to convince him to commit suicide.

Source: FBI, Public Domain.

In the 2000s, after 9/11, the New York City Police Department conducted a decades-long illegal surveillance program targeting the Muslim community. After 2002, the New York City Police Department’s Intelligence Division engaged in the religious profiling and suspicionless surveillance of Muslims in New York City—even though the program was struck down as unconstitutional.

And today, we see immigration and Customs enforcement in the U.S. using powerful technology, including automated license plate readers, cell snooping devices, and facial recognition to target immigrants for deportation.

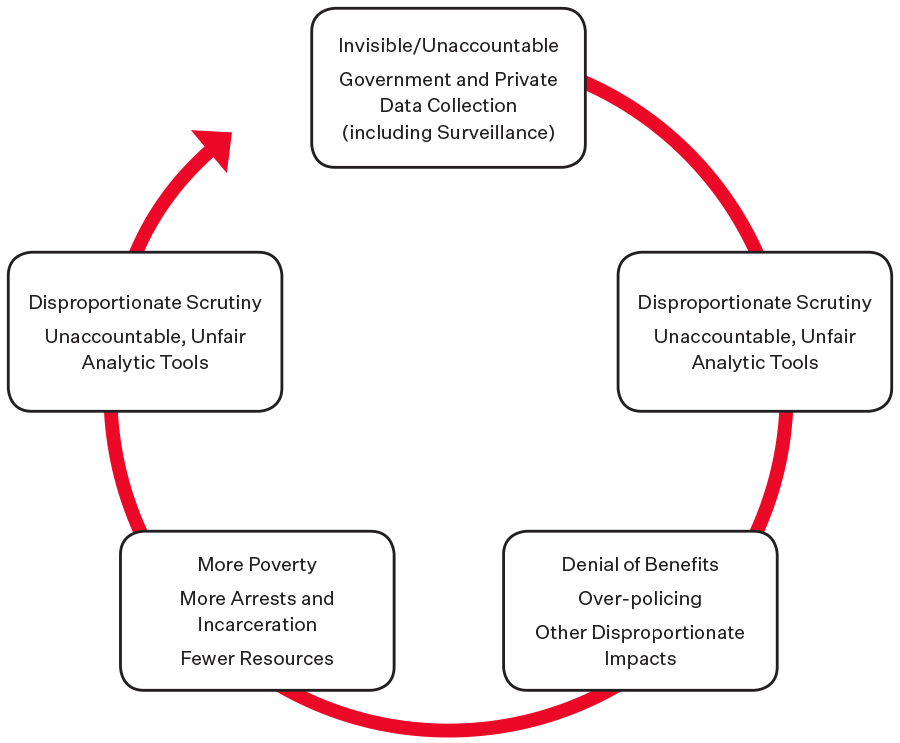

This diagram demonstrates a technology targeting cycle in which technologies that are not built by communities, and are invisible and unaccountable to communities, cause disproportionate scrutiny of those communities, which lead to tangible harms, and those harms further create disproportionate scrutiny.

Technology targeting cycle.

Communities aren’t at the decision-making table.

The issue we have identified through these historical examples is that communities that are most impacted have been rarely engaged in the creation and deployment of surveillance technologies. Those who build the technologies are data scientists and technologists, but those who are impacted by the technology are communities. So, the key questions we need to ask are: Who defines what the problems are that technology purports to solve? And, importantly, who has the power to decide if those technologies are built and how they’re deployed? What would it take to ensure that most of the power resides within the communities? And what would it take to make sure that these communities can determine the trajectory of technology?

What does community-centric tech policy look like?

I’m going to present examples of how we’re working to build community-centric technology in Washington. The goal behind the technology policy work we’re doing is rooted in redistributing power to make sure that new policies explicitly put communities in the driver’s seat. These policies include:

– Redistributing power;

– Centering equity/voice of impacted communities;

– Creating transparent and accountable processes;

– Questioning assumptions, and

– Creating opportunities to say “no.”

Over the course of the past years, we’ve seen a growth in a multi-sector movement to create community-centric technology and community-centric technology policy, comprising groups including impacted communities, the Tech Equity Coalition, Mijente, Athena (Amazon-specific), technology workers/labor, climate change activists, and antitrust groups.

In Seattle, we have built what we’ve called the Tech Equity Coalition, which is composed of representatives of organizations that represent historically marginalized communities and communities that have been impacted by surveillance, such as immigrants, religious minorities, and people of color. This very diverse group of people work to push technology to be more accountable to them.

A key piece of the work the Tech Equity Coalition has been doing is advocating for and implementing surveillance laws like the Seattle Surveillance Ordinance. This is a first-of-its-kind-law in the U.S. that requires public oversight for government use of surveillance technologies. This law was first passed in 2013, but suffered from an overly broad definition of surveillance technology, overbroad exemptions, and a weak enforcement mechanism that did not hold agencies accountable to comply with the law. The law was amended in 2017 and 2018 to rectify these problems and to create a community-focused advisory working group tasked with providing privacy and civil liberties impact assessments of different technologies.

This law is intended to be a vehicle to allow communities to directly influence surveillance technologies, rather than have these technologies just happen to them. The Seattle Surveillance Ordinance is a vehicle for not only community engagement and capacity-building, but also lawmaker education and engagement with communities.

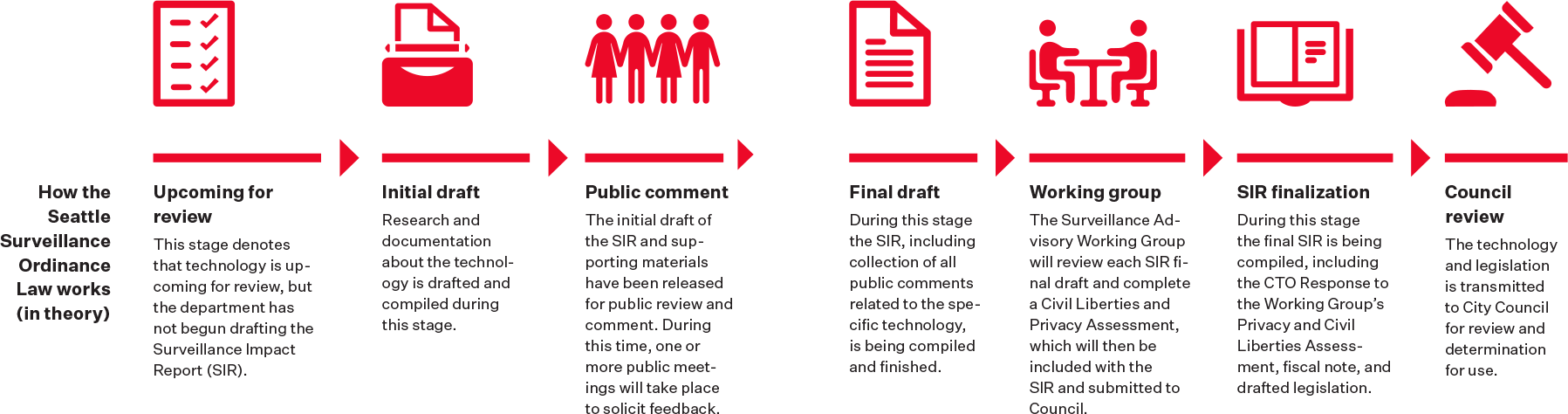

The diagram on the next page is a brief overview of how the law works in theory: every agency using a surveillance technology in Seattle must write a Surveillance Impact Report detailing how the technology is used and submit it to the public. The public then has a chance to comment on those technologies. Those public comments are compiled and the community advisory working group has a chance to review those comments and make final recommendations to City Council, which are the lawmakers that decide what laws are passed in Seattle.

We’re currently in the implementation process and we’ve reviewed a little over half of the technologies on the master list. Some technologies we’ve reviewed include the Seattle Police Department’s Automated License Plate Reader System (ALPR) and CopLogic system, as well as the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT)’s Acyclica sensor system. We’ve had a lot of successes and challenges.

One success of the Ordinance has been our ability to learn a lot of new information about surveillance technologies in use by government agencies. We’ve had a chance to see what technologies exist and assess the privacy and civil liberties implications of their use. This transparency is integral to building accountability. One of the technologies we’ve learned a lot about is Acyclica, a sensor used by the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT). For example, we learned that SDOT didn’t address important questions about Acyclica in its Surveillance Impact Report, such as questions around data ownership and retention.

But a challenge has been that so far it hasn’t been an opportunity to actually say “no” to a technology, even if we are able to provide recommendations. In addition, transparency is not accountability, and we’ve had to deal with all the logistics of engaging with the Ordinance, including limited community resources, uncooperative policymakers, complicated reports and technologies, and a very slow process.

Another example of work the Tech Equity Coalition has been engaging on is statewide laws like a face surveillance moratorium bill, which is a Washington state law that we are currently pushing forward. We helped introduce this bill last year in our legislature as an effort to press pause on the use of racially biased, inaccurate, and deeply flawed facial recognition technology. Our aim is to give impacted communities a real chance to say “no”—to decide if, not just how, a powerful technology should be used.

To do this work in building power within communities to advocate for technology policies that are accountable to them, we have been collaborating on community capacity-building projects with the Tech Equity Coalition. These projects are aimed at complementing the existing expertise that impacted communities already bring to the table, because as I’ve highlighted earlier, technology has always impacted these communities.

Community capacity-building projects

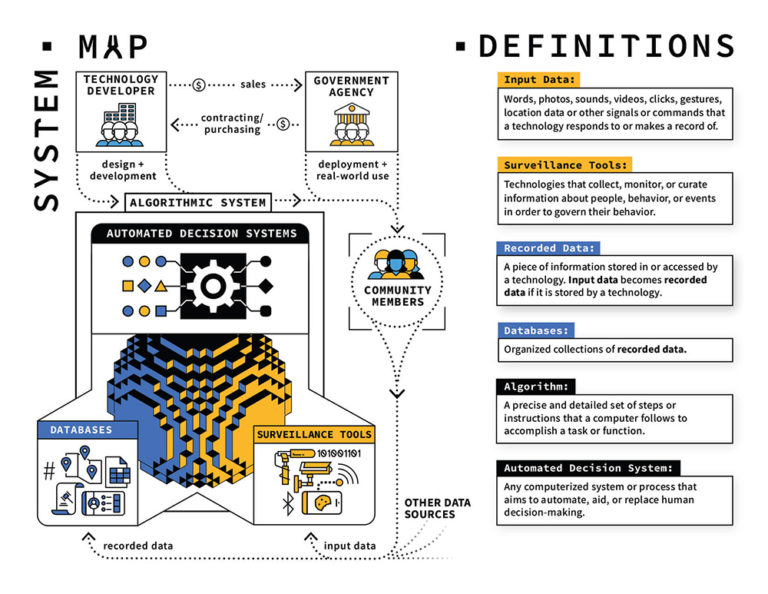

The first community capacity-building project is the Algorithmic Equity Toolkit, which seeks to help folks easily identify and ask important questions about AI-based automated decision systems. We collaborated with the Critical Platform Studies Group to build an initial version of the toolkit.

A component of the Algorithmic Equity Toolkit.

Source: Algorithmic Equity Toolkit, available at: https://aekit.pubpub.org/

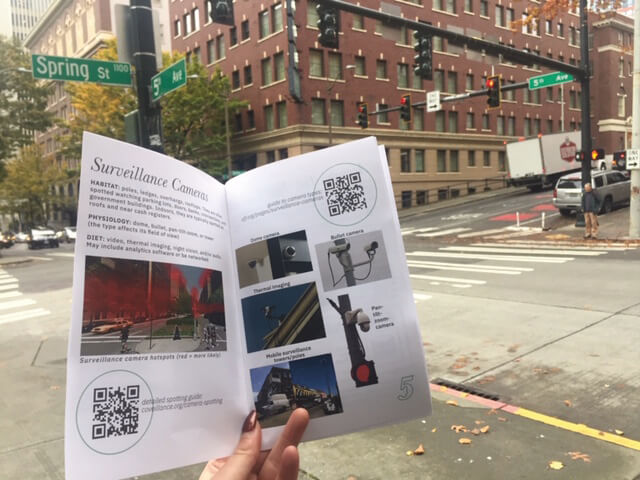

The second community capacity-building project is a countersurveillance workshop toolkit that we’re collaborating on with the coveillance collective. A countersurveillance workshop toolkit is designed to help communities host their own workshops and disseminate information about the wider surveillance ecosystem. We hosted two pilot workshops last fall, and we’re working with members of the Tech Equity Coalition to build upon those pilots.

A field guide for spotting surveillance technologies from a pilot workshop held in Seattle, Washington.

Source: The coveillance collective’s “Field Guide to Spotting Surveillance Infrastructure”, available at: https://coveillance.org

So, with that brief overview of the work we’re doing in Washington to build community-centric technology policy, I’ll leave you with a few key takeaways.

– Communities are really the ones that are best placed to identify and define problems for technology to solve;

– Communities are keenly aware of technologies’ impacts, even if they’re not using technical language to describe them;

– Life stories and experiences are very valuable, and they’re not just valuable once you label them as community data; and

– Community organizations and members are willing and eager to lead.

And, I’ll leave you with a few key questions to ponder. Not is this technology good or bad? But:

– For what purposes are we building technology, and with what rules and values?

– Who will be impacted? Are they in the room? What other collaboration structures can we create?

– Who gets to say “no”?

– Beneficial for whom? Who defines benefit?

Finally, I’ll leave you with one last question: What would it mean for those with the least power in conversations about technology to have far more or even the most power in the future of their design and implementation?