EN PT/BR

Exch w/ Turkers Project: approximations, individualizations and resistances

Bruno Moreschi, Guilherme Falcão

& Bernardo Fontes [GAIA, c4ai, Inova USP]

[Bruno Moreschi]

Before starting the presentation of the project, I would like to offer the context from which the project arises1. The Group on Art and AI (GAIA) started from an artistic residency that I began in March 2019 at C4AI, Inova-USP—Innovation Center of University of São Paulo, Brazil. Initially it was supposed to be just a period of artistic work with the staff of this center, but the lack of critical projects related to digital infrastructures seemed so great that, stimulated by the director of C4AI, the professor at USP Polytechnic School Fabio Gagliardi Cozman, and by artist and professor at USP Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism Giselle Beiguelman, little by little we created a larger network with more researchers, from different areas of knowledge, but with a common interest: discussing AI in a nonabstract way, locating and problematizing its elements, organizations and social implications. The logic of this follows a mix of reverse engineering with institutional criticism2.

Instead of recounting all of our current research projects (there are already seven projects in progress), we decided to focus on a specific project related to remote workers who, in a precarious way, train and maintain AI systems. I don’t know if everyone knows who the turkers are, our focus for this presentation.

Currently, there are already about 500,000 people who perform digital jobs on the Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) platform, maintained by the United States company Amazon. Turkers at AMT are responsible for performing microtasks that computers cannot efficiently perform, known as HITs (Human Intelligence Tasks). They are varied and can include, for example, text transcription, information search on the web, filling out surveys, and image description for projects such as ImageNet (Gershgorn, 2017).

An investigation by Difallah et al. (2018) shows that 75% of them are from the U.S., 16% from India and the remaining 9% from other countries. It is estimated that 2,000 to 5,000 workers can be found on the platform at any time (Ipeirotis, 2010). The mass of workers in this underground of technological practices grows every day and is considered “the final telos of algorithmic work” (Finn, 2017). This is the new achievement of the algorithmic capitalist economy, that of the “non-place” of work, a territory as diluted as it is difficult to regulate. Researchers use terms like “infoproletariat” (Antunes & Braga, 2018; Grohmann, 2018) to characterize the group of these workers. The turkers’ opportunity to get to know and establish contact with their working peers is practically nil, which prevents the group from organizing around labor regulations, for example.

Our project is in dialogue with the ideas of researchers like Gray & Suri (2019), in particular the idea that the total automation of “smart machines” is not a reality, since a considerable part of their functioning is only possible due to two related practices of the capitalist system: first, a wide exploitation of natural resources; second, a massive use of several human workforces.

Our interest here is in the human, and in the way that their work is exploited for processes related to the field of AI. In the project we present here, Exch w/ Turkers, the attitude was to approach these workers in a logic complementary to the many quantitative and demographic studies on the subject. Our complement here comes from the decision to approach some of these humans in specific ways, valuing their subjectivities. In short, we want to speak about this army of workers, but walking through the trenches, following the concept that a social group is formed by individuals united by certain points in common, but also diverse based on their individual beliefs, gender, race, specific geographical locations (even more so in the case of a group that is constituted in the online environment), etc.

This more unique approach allowed us not only to access their individual realities, but, because of a more intimate contact, also speculate on new collective realities with these workers. With Exch w/ Turkers we want to highlight how part of the AI systems are, in fact, not processes resulting from “intelligent machines,” but machines with intelligent humans.

The AMT home page, which promises constant work, makes very explicit Crary’s (2016) ideas about late capitalism and its context of consumption, work, sharing, and availability online 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Homepage of the Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) platform.

Then, we have a second page of the website, the main one of AMT, which lists the microtasks available—momentary jobs that almost always offer very low wages (it is common to pay a cent of a dollar for a service) and short periods of time to be accomplished. In addition to the low remuneration, we also have here a lack of belonging among the turkers and what they are helping to build and/or maintain. HITs that describe what their requested actions will be used for, or even a geographical or conceptual context of the project that relates to the work offered, are rare. In essence, the workers here don’t know what exactly they are building. I consider this a practical case of what Marx (2010) calls externalization (Entausserung) that makes work not only become something with external existence, but also that exists outside the creator.

AMT’s page with a list of available HITs.

https://worker.mturk.com/. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

To better understand what kind of tasks are offered at AMT, here are two lists. This material is part of an investigation carried out in conjunction with PhD student Gabriel Pereira (Aarhus University, Denmark), professor Fabio Gagliardi Cozman (Polytechnic School, USP) and graduate student Gustavo Aires Tiago (Social Sciences, USP) on Brazilian workers in AMT. In the article we wrote together, we discussed how these Brazilians are an under-underclass of turkers, since they are prevented by Amazon from receiving their remuneration directly, which makes them even more exploited than other turkers (Moreschi et al., 2020). The first list is a set of HITs considered strange chosen by these 149 Brazilian turkers interviewed:

“Analyze images of zebras”; “play video games for one hour”; “repeat what the voice of Google and Alexa say”; “watch movies and rate them”; “identify flowers and fruits in Brazilian plants”; “draw boxes on lab rats in different pictures”; “mark body parts of people fighting”; “answer true or false on a questionnaire about marijuana”; “mark which employees in photos were wearing helmets”; “locate hard-to-find business addresses on their original websites”; “make facial expressions on the computer camera”; “map furniture and floors in a kitchen”; “modify phrases in the imperative such as ‘play pagode [Brazilian genre] music’ to ‘press play to pagode music in the living room’”; “rate tweets on Twitter”; “transcribe commercial receipts”; “describe what you see in a photo of Tom Hanks”; “take pictures of one’s eyes”; “film forty hand gestures”; “dance in front of the camera”; “count how many grains of corn were in a corn cob”; etc.

The second is a list made by these same Brazilian turkers, but which now presents some of the tasks that involved pornography, violent content and/or invasions of privacy broadly speaking:

“Push a button to send sms to other people”; “sexual image analysis”; “moderate photos from adult dating sites”; “produce videos getting inside and leaving one’s house”; “take pictures of pants, often with views that include intimate regions”; “watch pornographic movies up to thirty minutes long”; “play a game on the mobile phone while one’s face is being filmed”; “categorize images from pornographic sites”; “write an erotic story”; “upload personal photos”; “describe images of dead people, full of blood”; etc.

Regarding the lists above, it is important to note that there is no psychological support offered by Amazon to these workers. Those who choose to do these tasks must go through an absurd and inefficient control that basically consists of clicking on an agreement button, claiming to be someone of legal age and aware that they may see something pornographic—a way for Amazon and the requesters to protect themselves from lawsuits.

This, therefore, is the context in which the Exch w/ Turkers project is inserted. Now, I invite the designer Guilherme Falcão to explain a little about the construction of a virtual space independent of AMT to get closer to the selected turkers.

[Guilherme Falcão Pelegrino]

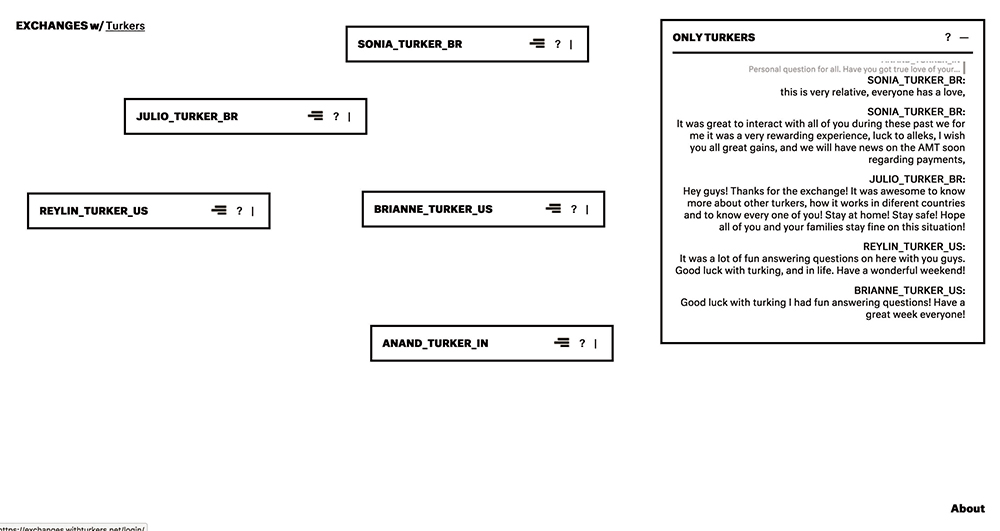

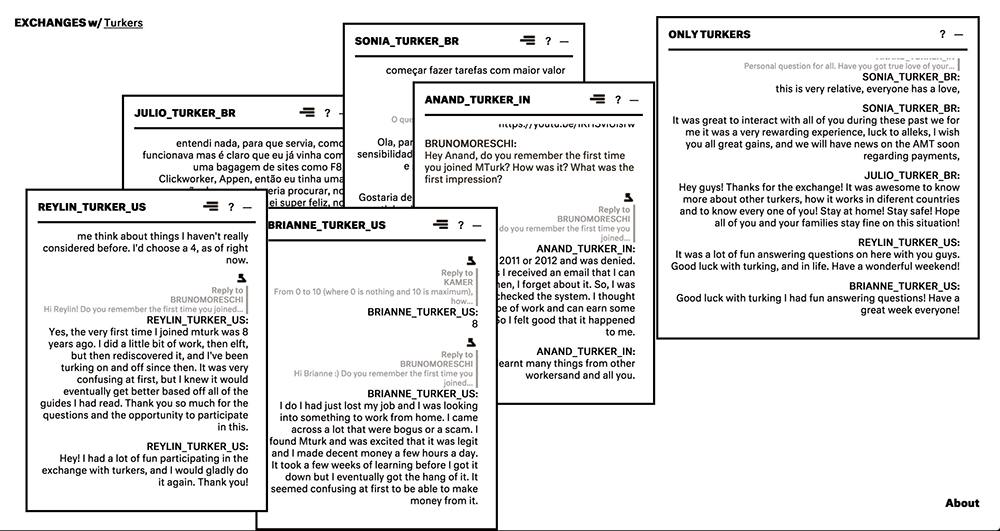

The idea was to give these people a voice. For this reason, the project was thought of as a dialogical environment, including specific chats for the five selected turkers and a collective chat, where only these turkers could type, but which could be seen by all those who enter the website. We wanted to minimize the anonymity of these people who stay at AMT pressing buttons and answering questions of different complexities. We wanted to bring them to the surface.

I have worked with Moreschi for at least four years, and in this long process we have built some premises for how our projects work in terms of design and visual organization. What we built this time is the result of this: an interface that has few elements and is essential, so to speak. In our projects, we prefer to use a typography designed from an interpolation of several typographies that are intended to be neutral, drawn throughout the history of design—it is called Neutral, which is almost an anecdote for us.

Returning to the project, it also has a desire to try to return a bit to that more “innocent” idea of the chat room of the 1990s, early 2000s, when we used to enter a chat room to talk with distant people, scattered around the world, or maybe just down the street. Based on that, I designed these windows that one can easily manipulate: expand and enlarge, move them on your desktop, and even create chaos with a lot of windows open at the same time.

Main page of the Exch w/ Turkers website—with the turkers’ chat windows closed.

Main page of the Exch w/ Turkers website—with the turkers’ chat windows open.

Or one can concentrate on collective chat—where only turkers can type. In addition to these features, one thing that we thought was important to insert was a question button in each of the turkers’ window, which opens the profile of the participating worker. Through these profiles, the visitor can learn a little about who that person is, who works on a daily basis on the Amazon platform. I present the profiles of the five turkers selected for the project—two Brazilians, two North-Americans and one Indian.

The project also has a bit of this black and white playfulness—which is also something very striking about the collaborations that Bruno and I do, this reduction of information to a minimum. When you enter the website for the first time to register, everything is black, once you log in it is all white. There’s a little bit of this idea of “you’re outside looking in, you’re inside looking out,” and what it’s like to be in and out, as you get a little closer to who these people are and you know a little more about them.

Profile of the turkers in their chat windows.

Finally, it is important to note that this project was done in partnership with aarea, an online platform that features works of art designed especially for the Internet.

[Bernardo Fontes]

I was responsible for the process of programming and creating the website, in partnership with the programmer Luciano Ratamero. Turkers are people who are in a position of extreme exploitation in capitalism. And, of course, this has psychological impacts on these workers. This has always been one of the concerns: In addition to the payment being something fairer than it is in AMT, the interface we created should make it easy for each turker to participate. We considered how to make this project feasible without it being another channel for that person to be anxiously having to press “CTRL + R” on the page to see if there is a new message and so on. To avoid this problem, we made the decision that we would notify them in an asynchronous and noninvasive way using emails—always a single message per day, consolidating all questions sent by visitors. Therefore, the website may give the false impression that you send a message and, automatically, a turker will respond, but that is not what happens. The turkers had 24 hours to reflect on the questions, and only then respond. The logic of time is yet another layer of AMT that we subverted in this project.

Finally, our group believes that we need to rethink how machines are being trained by humans, understanding how the precariousness of the turkers’ work directly interferes with the quality of AI systems that are built. If they were more valued, could these turkers not offer a better quality of work and thus build better technological systems? Here lies a fundamental point for those who aim for more ethical, fair, and truly efficient digital infrastructures.

1 Part of this text uses excerpts from previous research carried out by Bruno Moreschi, in particular from the article “The Brazilian Workers in Amazon Mechanical Turk: Dreams and Realities of Ghost Workers”, written in collaboration with Gabriel Pereira and Fabio Gagliardi Cozman, and published in the journal Contracampo (UFF), v. 39, n. 1 (2020)

2 As nothing is actually created alone in the field of academic research and the arts, it must be noted that GAIA would never be possible without its collaborators. They are people committed to building a critical movement that tries to understand the transformations caused or intensified by current technologies beyond the reactions already disseminated by the Global North. Three sources of support need to be mentioned here: the Center for Arts, Design, and Social Research (CAD+SR, Boston), the collector Pedro Barbosa, who supports GAIA and some of its researchers, the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo (FAUUSP), and the aforementioned professors Fabio Gagliardi Cozman and Giselle Beiguelman, the latter sharing with me the coordination of GAIA.

REFERENCES

ANTUNES, Ricardo (Ed.). Riqueza e miséria do trabalho no Brasil IV. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial, 2019.

CRARY, Jonathan. 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. New York: Verso Books, 2013.

DIFALLAH, Djellel et al. Demographics and Dynamics of Mechanical Turk Workers. Anais da 11th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Los Angeles, 5 a 9 de fevereiro de 2018.

FINN, Ed. What Algorithms Want. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017.

GERSHGORN, Dave. The data that transformed AI research—and possibly the world. Quartz, 26 jul. 2017. Disponível em: https://qz.com/1034972/the-data-that-changed-the-direction-of-ai–

-research-and-possibly-the-world/ . Acesso em: 17 out. 2019.

GRAY, Mary L.; SURI, Siddharth. Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley From Building a New Global Underclass. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019.

GROHMANN, Rafael. Materialidades do trabalho digital no Sul Global e invisibilidades comunicacionais. Comunicação & Educação, v. 23, n. 2, pp. 153-163, 2018.

IPEIROTIS, Panos. Demographics of mechanical turk. NYU Working Paper No. CEDER-10-01, New York, 6 abr. 2010. Disponível em: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1585030. Acesso em: 15 jul. 2019.

MARX, Karl. Manuscritos econômicos-filosóficos. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial, 2010.

MORESCHI, Bruno; PEREIRA, Gabriel. COZMAN, Fabio G. Trabalhadores brasileiros no Amazon Mechanical Turk: Sonhos e realidades de trabalhadores fantasmas. Contracampo, Niterói, v. 39, n. 1, pp. 44-64, abr./jul. 2020.