EN PT/BR

Calendar of dissenting images: a graphic memory of Brazilian politics in Instagram

I will introduce you to the project Dissident Calendar, a website that represents the partial result of my Ph.D., which is in progress in the Graduate School of Design at the University of São Paulo. The project is supervised by professor Giselle Beiguelman and is an interdisciplinary work that I have been doing during my residency at GAIA (Group on Art and AI), at Inova-USP. And it counts with the incredible partnership of data scientists Vinícius Akira Imaizumi, Gustavo Poletti (Poli-USP), and Gustavo Braga (Insper), under the supervision of professor Fabio Gagliardi Guzman, a great encourager of this research network. And the independent programmer Marcelo Villela Gusmão, responsible for the website’s front end.

The Dissident Calendar is a project that discusses the graphic memory of the main sociopolitical events in Brazil since the inauguration of President Jair Bolsonaro on January 1, 2019. The discussion is done by mapping the aesthetics of the images in the Instagram database. It is a curatorial and critical work that investigates new aesthetics of the images produced to be broadcast on the networks. The way these images are produced, mediated, and transmitted today, all this aesthetic production is at risk of being lost in the media flow. They are cards (images-messages) created in the heat of political events not only by designers and artists but by citizens engaged in various activist causes.

The volume of images produced during the first and second rounds of the presidential elections in 2018 was surprising and the social networks truly represented a powerful activist vehicle, directly related to the demonstrations that took place on the streets. To archive and analyze this new aesthetic vocabulary, we used artificial intelligence and machine learning as essential tools to classify this data production. Artificial intelligence allowed me to work with a much larger sample of images, managing to expand the aesthetic vocabulary to be analyzed, as I had access to images that would never be visualized if I was working just from my newsfeed, looking only at the images that Instagram’s algorithm was “directing” to me.

One of the main differences of the Dissident Calendar website is that it organizes this heterogeneous production, produced collectively, in a chronological visual narrative, in parallel to the main political events in the country. The hashtags established as a search filter were considered the most representative of the divergences and collective and poetic manifestations of all of us, through the lens of visual narrative design. We selected the following hashtags: #desenhospelademocracia (#drawingfordemocracy), #designativista (#activistdesign), #coleraalegria (#wrathjoy), and #mariellepresente (#mariellelives).

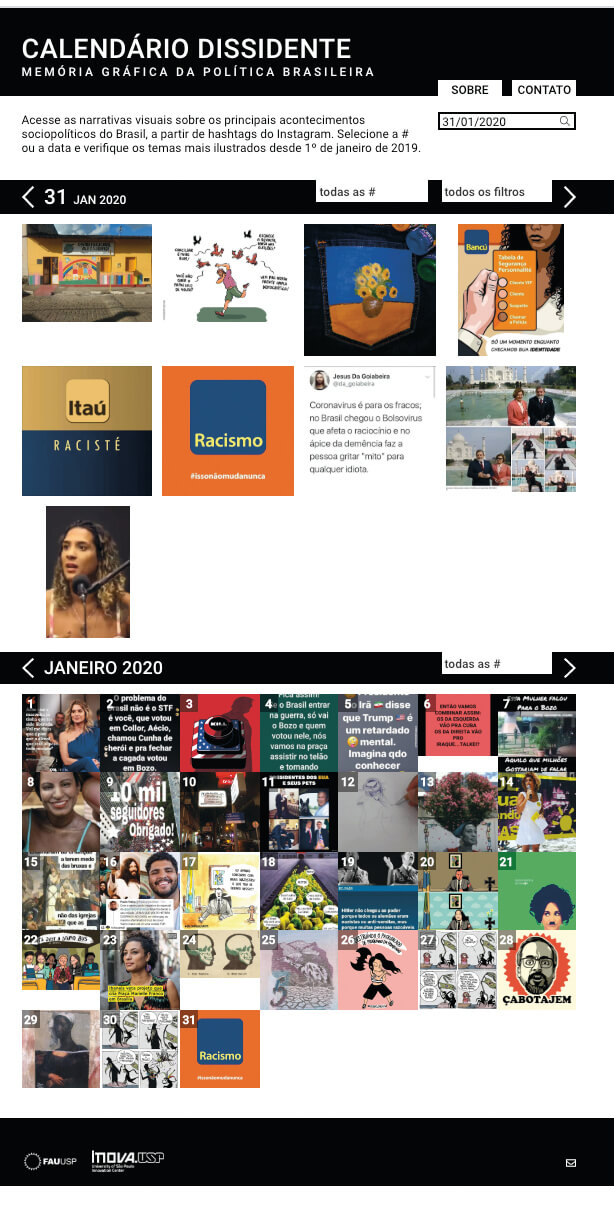

Dissident Calendar homepage.

It is important to remark that the hashtag #mariellepresente was created before the elections and after the assassination of the politician Marielle Franco1, in March 2018. However, we maintained the data visualization of this hashtag because it is related to many political and social issues—topics concerning LGBTQ rights, the female protagonism and the fight against racism. This data enhances the critical nature of the research, adding a social layer to the analysis of these narratives.

#mariellepresente (mariellepresent).

– – –

Before entering the technological and functional aspects of the Dissident Calendar project, I digress to point out more philosophical artistic and curatorial strategies. I would like to quote two key thinkers who investigate the contemporary image, Didi-Huberman and Rancière. In Uprisings, Didi-Huberman’s homonymous text and exhibition, he names the dissenting images as “image-desires,” a very poetic term that reflects this participative will of citizens to produce and convey images: “They are image-desires, capable of serving as models for crossing borders” (Didi-Huberman, 2018, p. 7). This concept of “image-desire” helps us answer why these images ultimately touch us and move us to think of dissenting battles’ fragility and the strength of art as an instrument and as a voice for new messages. Rancière, in his notorious The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, states that “the aesthetic revolution is, above all, anyone’s glory.” This brings us to the new regime of arts and digital images produced by anonymous artists: the networks’ users.

– – –

The analysis of these images and the issues about their archiving go through processes of qualitative and quantitative analysis. First, we made a careful selection of image sets based on aesthetic criteria to train the machines. In this process, I became the turker and hired myself to select six thousand images related to the six aesthetic categories previously defined for labeling. From the visual syntax, format, and language of these images, I established seven aesthetic parameters to classify them in the following categories: Factual; Memes, which is a subcategory of Factual; Digital Illustration; Manual Illustration, Digital Typography; Vernacular; and Appropriation. The labellers were developed by Inova-USP’s team. And we consider it an unprecedented work because we do not use any classifier that is already in the market, no Python off-the-shelf model. These classifiers do not have a commercial or surveillance bias.

Images used for machine training, classified in the categories Factual; Memes, which is a subcategory of Factual; Digital Illustration; Manual Illustration, Digital Typography; Vernacular and Appropriation.

We then move on to the presentation of the pages and the possibilities of navigation of the site: The calendar is streaming, the system tracks the six main images linked to the four hashtags for 24 hours.

The system is updated four times a day, so the daily calendar display changes according to the number of postings under the same hashtag. The most liked and shared images are published. And we created an AI to identify the repeated images.

At the top of the homepage we publish the most liked and/or shared images of the day.

The user can also browse through thematic searches. The system captures the original captions of Instagram images and indexes to the main themes. We created a database of keywords in order to cover as many activism as possible. We tracked a thousand of the more significant words in all the subtitles and created a code for this function. From these thousand words, we selected 55 tags:

amazonia (amazon), aquecimento global (global warming), arte (art), bolsonaro, brasil (brazil), brazilresists, brumadinho, caixa2dobolsonaro (bolsonaro’sslushfund), cirogomes, crime ambiental (environmental crime), cultura (culture), democracia (democracy), desastre ambiental (environmental disaster), dilma, direitoshumanos (humanrights), ditaduranuncamais (nomoredictatorship), diversidade (diversity), doria, educação (education), educaçãoinclusiva (inclusiveeducation), eleicoes2018 (elections2018), eleições2018 (elections2018), elenunca (neverhim), esquerda (left), fascistas (fascists), feminismo (feminism), foratemer (temerout), fumaça (smoke), golpista (coupplotter), grevegeral (generalstrike), haddad, história (history), homofobia (homophobia), impeachmentbolsonaro, indígenas (indigenous), justiça (justice), lgbt, lgbtq, liberdade (freedom), lula, lulalivre (freelula), machismo (sexism), mariellevive (mariellelives) , meio ambiente (environment), mexeucomumamexeucomtodas (messedwithonemessedwithall), mineração (mining), moro, movimentonegro (blackmovement), mulherescontrabolsonaro (womenagainstbolsonaro), mulheresnapolitica (womeninpolitics), mulheresunidaspelademocracia (womenfordemocracy), negra (black), ninguemsoltaamãodeninguem (reachoutandholdoneanother’shands), oleo (oil), petroleo (petroleum), praia contaminada (pollutedbeach), previdência (social security), queimadas (fires), quemmatoumarielle (whokilledmarielle), racismo (racism), redeglobo, reforma trabalhista (employment reform plan), resistencia (resistance), sociedade (society), tsunamidaeducação (educationtsunami), vazajato (carwashoperation), vidasnegrasimportam (blacklivesmatter).

All published images are credited from the username that published it on Instagram (you can access the author’s page). Since several images are viralized and repeated, we have adopted the criterion of crediting the first publication referring to that image. By clicking on a highlighted image, you have access to the image’s author.

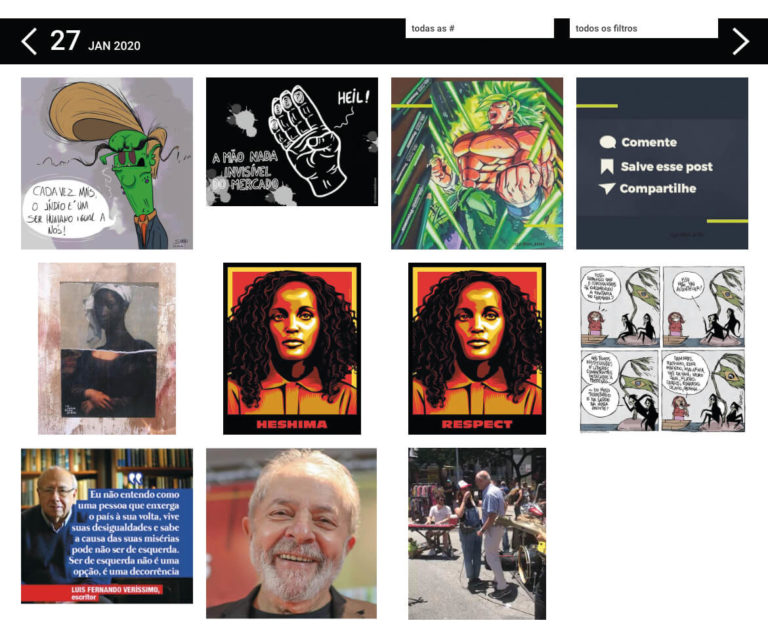

For example, in Figure 5, you can see an artwork by designer and illustrator Cris Vector depicting Ugandan environmental activist Vanessa Nakate. She participated in an international event along with Greta Thunberg and other activists, but she was cut from the event’s official photo. Cris Vector, the activist designer, wanted to give visibility to this fact by adding to the image of Nakate the word “heshima,” a word from the Swahili language, which means “respect” and also “dignity.” (Swahili is one of the official languages of Uganda.)

Ugandan environmental (and Black) activist Vanessa Nakate suffered discrimination in an international event and was portrayed by Cris Vector. In the image, the designer included the word “heshima,” a Swahili word that means “respect” and also “dignity.”

Browsing and searching the keywords, we access other images tagged with the words “black,” “racism,” “marielle present,” and “black lives matter.” In this case, the keywords were inserted by the author of the post and not all images related to racism will present this tagging, which is unfortunate because the sampling would be wider. Another feature of the site that might be highlighted: the user can always access the link to the original post, leading them to meet the authors and other illustrators, other people who are producing these dissident images.

Phase two

The second phase of the project, which is not yet online, will present a curatorship of images assisted by artificial intelligence. These are the visual narratives edited by the six image labelers. The site will publish some galleries of factual images, digital illustration, digital typography, manual illustration, vernacular typography, and appropriation.

Another interesting aspect of the discussion around dissenting images in this project is the question of visual language: what is global and what is local? And another question I would like to explore is the use of our classifiers—trained to analyze the Brazilian dissident imagery—with other international hashtags. It would be interesting to find out what visual and stylistic features are common to posts in Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, the United States, etc. Is there a dissident aesthetic common to activist images in Latin America? In the United States? In the Global North? In Europe?

In Figure 3, with the appropriate images, we see the iconic Obama campaign poster Hope created by Shepard Fairey, appropriated with the phrase “Yes we can” and reappropriated with the images of Bolsonaro “Ele não” [Not him] and Marielle. In another example, Andy Warhol’s iconic serigraphic work with Marilyn Monroe’s face is reappropriated with Marielle’s image. [FIG. 3]

It is quite a big challenge to make a machine training set to label the appropriate images, but we still have this in mind. After all, cultural appropriation is one of the main characteristics of the remixed language of social networks, of digital visual culture. And the idea is to bring this to the website thinking about the design focus.

To conclude, I present a robot-generated image. It illustrates the visualization of images labeled by artificial intelligence. Working with AI means working with many numbers and parameters and graphics, and I have a visual arts and design background. So, visualizing the error was very important for the understanding of the whole machinery process: Why does AI make mistakes? Where and why? And thanks to the multidisciplinary work with Gustavo Poletti, we were able to apply the MMD Critic model, developed by Been Kim’s team at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Kim, 2016). The model has been customized to run with our markers and point out the critical details of the classification.

The visualization of the images labeled by the MMD Critic model.

The images’ resolutions are super high: 120 dpi. And we were able to identify some digital illustration images, the factual ones, and manual illustrations. The vernacular images, with handwriting, which require a cultural or intellectual repertoire, are not recognized and interpreted by the robot. Analyzing the accuracy, we began to study the 13% of error. And so we have been seeking solutions to improve the accuracy of our classifiers. They tend to make mistakes when the language is very remixed, composed of multiple languages. If we, as trainers of these machines, are in doubt when it comes to classifying the sets of images, hesitating to put them in a certain category, could you imagine a robot’s response?

Final considerations

I have a great concern about the subjectivity of machines’ interpretation of artificial intelligence. Can we talk about the subjectivity of the machine from images composed and interpreted by computer visions? I believe so.

It is essential to highlight how subjectivity is present in the interpretative successes of the machine trained for this project. It was trained and manipulated as a highly scalable classification extension and can recognize, select, and categorize in seconds various types of images, in large quantities. The data inferred as a visual reference have already undergone previous interpretation, and have been revised to serve as the aesthetic parameters of a given set of images. This step is crucial and in it resides all the responsibility and human power in manipulating the data for a given purpose.

In this sense, dealing with image classifiers constructed from aesthetic parameters puts us in a very peculiar situation where the curatorial strategy apprehends new information related to the analyzed images, from the hits and errors of the neural models. The models thus become partners in the task of visualizing and analyzing the languages of the posts from the network. And the visualization of this language, reconfigured and “re-represented” leads us to other discoveries and inquiries.

By navigating through the calendar months, we have a good reading, through images, a mosaic of visual languages—manual illustrations, documentary images appropriated from mass media, digital vector illustrations, and collages with remixed languages. We read the sociopolitical events through another language lexicon. The images produced and shared by many form a heterogeneous narrative, in terms of visual language, but unified in terms of message. A game of language, collective participation, addition, appropriation, affective exchanges, political positions, activism related to many themes, some places, and other places. There is a proliferation of common direction, of something that affects us and that we need to participate in this current, producing images, taking part in this game of language of communicating and expressing oneself through images.

It is up to us, researchers, designers, and artists, to ethically use machine learning tools to classify images. So, I say again that our attention is focused on the creation of computer vision models, from a critical and aesthetic methodology to work in the field of digital visual culture in which the Dissident Calendar is inserted. We hope that this methodology can contribute to other works in design, visual arts, humanities, and data science.

1 Editor’s note: Marielle Franco was a politician and human rights activist who was brutally assassinated in the city of Rio de Janeiro on March 14, 2018. Although the police investigations have not concluded, she may have been targeted for her outspoken critique of the militias in Rio, police brutality, and other human right abuses.

REFERENCES

BEIGUELMAN, Giselle. Memória da Amnésia: Políticas do Esquecimento. São Paulo: Edições Sesc, 2019.

CRAWFORD, K.; Paglen, T. Excavating AI: The Politics of Training Sets for Machine Learning. Disponível em: <https://excavating.ai>. Acesso em janeiro 2020.

DIDI-HUBERMAN, Georges. (Org.). Levantes. São Paulo: Edições Sesc, 2017.

KIM, Been et al. Examples are not Enough, Learn to Criticize! 29th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2016), Barcelona, 2016.

KRIZHEVSKY, Alex Ilya et al. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems – Vol. 1, 2012.

MANOVICH, Lev. AI Aesthetics. (2018). Moscou: Strelka Press, 2019

NAVAS, Eduardo. Regenerative Culture. In: Norient Academic Online Journal. Disponível em: https://norient.com/academic/regenerative-culture-part-15/. Acesso em abril 2020.

RANCIÈRE, Jacques. A partilha do sensível: Estética e política. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2005.